As I said in a previous post on men’s fiction, categorization has utility in fiction—just as it does in other mediums. In music, for instance, a fan of country music searching for some new tunes probably won’t appreciate hip-hop releases populating his search results. And vice-versa. In like manner, a reader looking for new techno-thrillers will find suggestions for shapeshifter romances to be a nuisance. For me, taxonomy is essential.

The recent furor over men, fiction, reading, and what books are being published arose over tradpub’s contempt for men, including potential customers/readers. Without consciously making the decision, I funneled the debate into one about men’s adventure fiction (MAF), specifically. Probably because I miss that category and its subordinate genres and frequently lament its extinction. (But is it actually extinct? Stand by for more on that.) But I’m not apologizing for where I took it. What happened to fiction specifically for men is a symptom of the bigger problem worth looking at—because that flavor of fiction could very well be part of a remedy, too.

In previous posts on this subject, some have responded with suggestions for books, and sometimes plugged their own, as happens pretty much anywhere this topic is discussed. First off, I appreciate the former and empathize with the latter. And I welcome more of the same. Nevertheless, I can’t help noticing that many books suggested do have an appeal for male readers, but are not actually “men’s fiction.”

I have no problem with unisex fiction, have read and enjoyed plenty of it. For that matter, I’ve also consumed fiction specifically targeted at a female audience, and enjoyed some of it. So don’t assume I’m advocating for a replacement of all fiction with that which appeals exclusively to men.

What I’ve noticed is that most people, myself included, have been a little sloppy in our definition of men’s (adventure) fiction. On a lark, I asked A.I. what sets this category apart from other genres. Its reply is below.

"Men’s adventure fiction" is a distinct subgenre that blends elements of action, suspense, combat, and often military or espionage themes, tailored to appeal to a male audience. Here’s what typically sets it apart from other fiction genres:

1. Action-Packed Plotlines

The core of men's adventure fiction is high-octane action. Explosions, firefights, hand-to-hand combat, and death-defying escapes are common.

These stories prioritize physical conflict and adrenaline-fueled scenarios over emotional or introspective storytelling.

2. Lone Wolf or Alpha Protagonist

The hero is often a rugged, self-reliant man—sometimes an ex-soldier, spy, mercenary, or vigilante.

Think Jack Reacher, Mack Bolan (The Executioner), or Rambo.

He operates with his own moral code, often outside the law or conventional systems.

3. Themes of Justice, Revenge, and Survival

Common motivations include avenging a wrong, protecting the innocent, or taking down powerful enemies (e.g., terrorists, cartels, corrupt governments).

It’s often a man-against-the-world scenario.

4. Pulp and Series Tradition

Many men's adventure books come in long-running series with numbered entries (like The Destroyer, The Executioner, Able Team).

They originated from pulp fiction roots and often feature formulaic but satisfying plots.

5. Military or Espionage Influences

Often intersects with military fiction, spy thrillers, and techno-thrillers.

Settings may involve war zones, covert operations, or paramilitary missions.

6. Minimal Romance, Maximum Grit

Romance is usually a secondary subplot (if it appears at all).

The tone is gritty, direct, and often unapologetically masculine.

That’s not a bad definition. Good job, you robot scum.

Some of this is contradictory (“lone wolves” in military/war fiction, for instance). And we may rankle at the idea that it’s formulaic, but I guess everything could be argued to be formulaic to one extent or another. And frankly, a lot of MAF (men’s adventure fiction) is undeniably formulaic. That’s probably why I don’t read as much Louis L’Amour as my father did. Some readers are more sensitive to formula than others; and some formulas are obviously appealing, or they wouldn’t be used as often. There are only so many story plots out there, after all. “It’s not the story you tell, but how you tell the story,” as the old axiom goes.

7. No Gender Confusion

I would add that the male characters are unabashedly masculine in MAF, while female characters are unabashedly feminine. This is a quality which sets it apart from every other flavor of literature.

The robot scum A.I. continues:

Comparison with Similar Genres:

Thrillers: May overlap, but thrillers can have broader appeal and more psychological or political complexity.

Spy Fiction: Can be more cerebral and focus on tradecraft (e.g., John le Carré) rather than just action.

Military Fiction: Focuses more on realism, tactics, and camaraderie, whereas men's adventure leans more on heroic exploits.

Pulp Fiction: Broader umbrella that includes horror, crime, sci-fi, etc.—men’s adventure is a specific strand of this.

I’m tempted to talk about Clancy, Cussler, and a dozen other tradpub authors right now, but to keep it from getting too long-winded, I need to narrow it down.

Larry Correia’s Monster Hunter International is one book which can be, and has been, branded as MAF before. Let’s see how it holds up.

Action-Packed Plotlines?

“Action-packed” is in the eye of the beholder. There definitely are some action sequences in the story. However, physical conflict was not the priority. The priority was the protagonist becoming an accepted member of the monster-hunting team, and winning the affection of the heroine. So, I vote “no.”

Lone Wolf or Alpha Protagonist?

Owen is not a lone wolf. This story, again, is about him finding a place on a team. But that shouldn’t disqualify this book anyway, unless the paramilitary adventures from the 1980s are disqualified as well…which they should not be. But is Owen an alpha? Not by any stretch—whether you define “alpha” according to anthropology, the socio-sexual hierarchy (SSH), or pick-up artists. On his best day, Owen is almost as macho as his love interest. There is a character who is closer to a true alpha, but he serves as Owen’s foil, somewhat of an obstacle to acceptance on the team, and competition for the love interest. Owen places Julie on a pedestal, which is not what an alpha does. So MHI objectively fails to meet this criteria.

Themes of Justice, Revenge, and Survival?

There is a sort of justice theme going on. Owen and his new allies are trying to save the world from the Cursed One. Something missing from the A.I. definition is a theme of protecting the weak and/or innocent. MHI has this and therefore meets this standard IMO.

Pulp and Series Tradition?

Obviously this book became the first in a series, which is not Correia’s only one. And there are mos def pulp elements. I don’t know if Correia has read pulp, but whether he was influenced directly or second-hand, the influence is there. MHI passes this metric, as well.

Military or Espionage Influences?

I’m not even so sure about this stipulation. And I’m not so sure how to judge it. There’s some cultural overlap between the military and gun nuts. This is fiction from a gun nut perspective, which was pretty rare in tradpub when it was published, and an aspect of the story I personally appreciated. But military/espionage influences…I’m not sure. No doubt Larry has read in those genres, so maybe that alone qualifies MHI.

Minimal Romance, Maximum Grit?

Owen’s infatuation with Julie is a subplot, but this is somewhat a gray area. What romance you find in classic MAF is rarely more than opportunistic flings with attractive women—or a series of such. Not too many MAF protagonists get one-itis for any particulary dame. Unless she is to become the victim of a villain, driving the aforementioned revenge theme. I’m not sure how to judge if this is “maximum grit,” either. I do think the protagonist’s insta-obsession with one girl is more than what you would generally expect in MAF. While not enough by itself to disqualify the book, it does cause me to lean against MHI’s inclusion in the MAF category.

The Metric A.I. Didn’t Mention:

MAF borrowed heavily from the classic pulps. For fans of the Snow White remake, this will sting a bit: women need rescuing, and not just in the pulps. It’s not as dramatic in real life, usually, but it’s common. Around the house, a woman constantly relies on some man or other to fix what breaks or wears out. She gets involved in altercations, and if she gets in over her head she will ask a man to resolve it—her husband, father, boss, a cop, or, as the story of our country confirms since 1919, Big Daddy Government. I know, I know: there’s no shortage of anecdotal ackshullies that run contrary to this premise. So let’s look at some of the aforementioned physical conflicts that occurs in MAF.

MAF heroes have to fight monsters, tigers, crocodiles, sharks, snakes, and dangerous men—sometimes with bare hands.

Recent history has provided countless examples of mediocre male athletes thrashing the best female athletes. Men and women are designed physically, psychologically, and emotionally different. Men are simply better suited to be hunters, protectors, and (sorry New Improved Snow White) rescuers—at least without decades of relentless cultural conditioning designed to quash any modicum of masculinity. An unabashedly masculine man will instinctively protect women and children. He will also provide for same (i,e: hunting, in a primitive scenario).

The entertainment industry has spent half a century programming society to believe that women have just as much, if not more, physical prowess than the best of men. Whatever their faults, the MAF authors did not try to push this fetish on their readers.

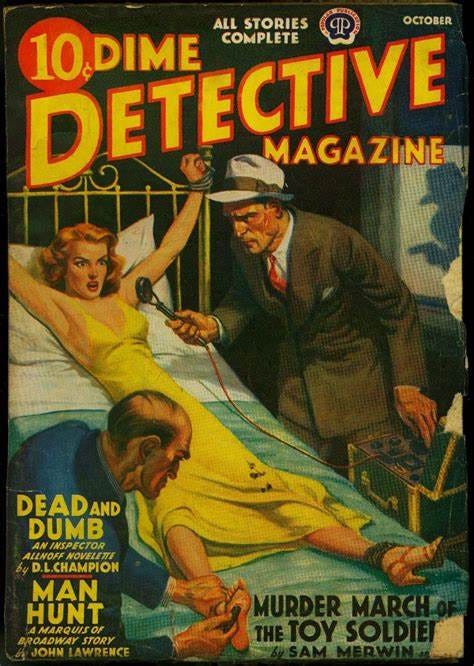

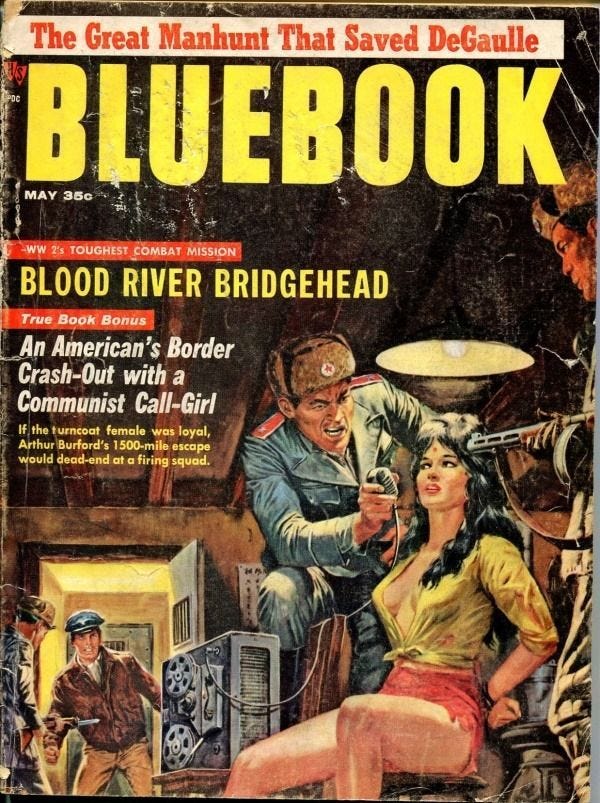

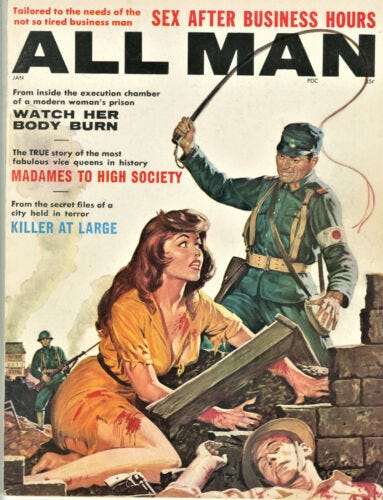

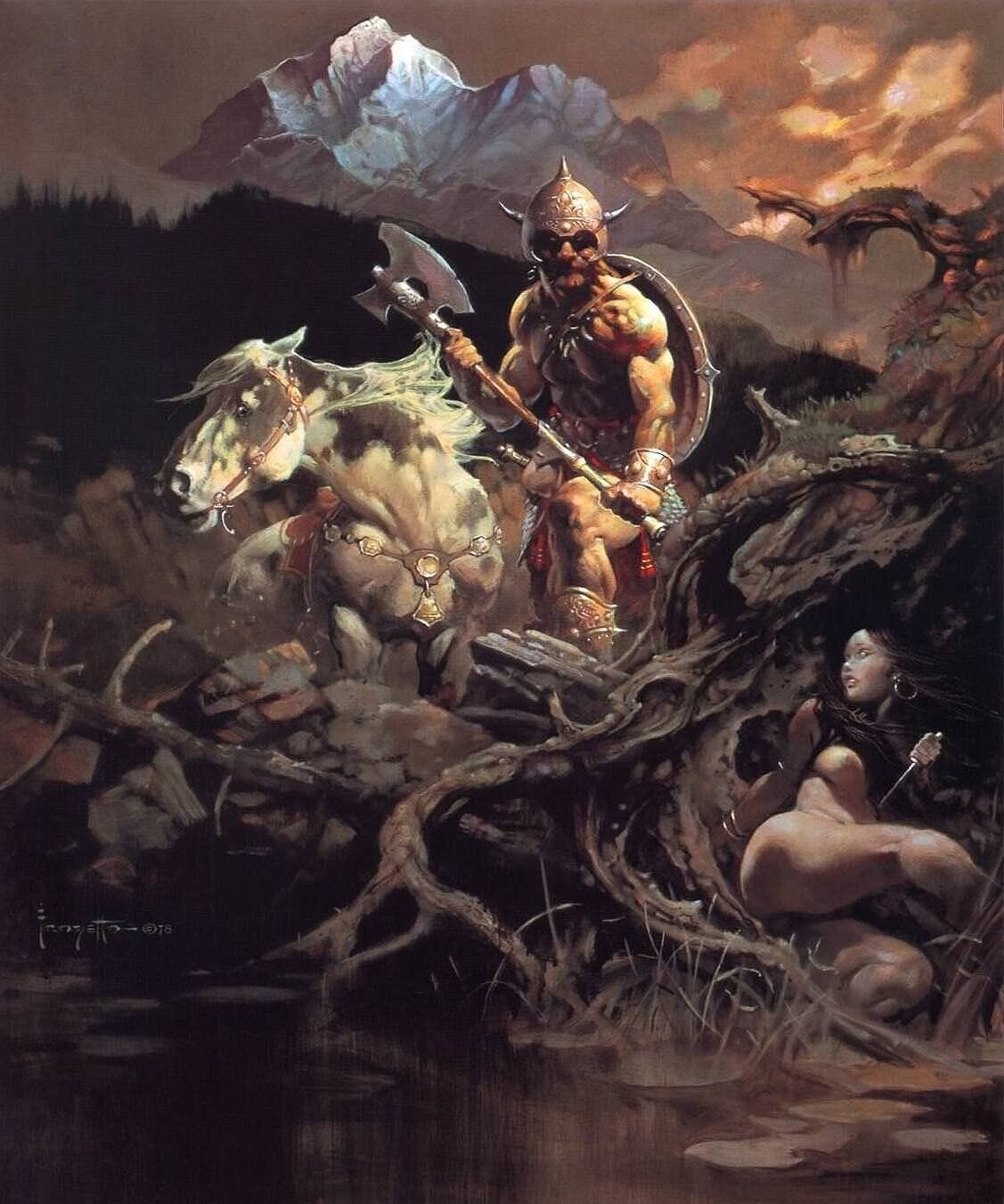

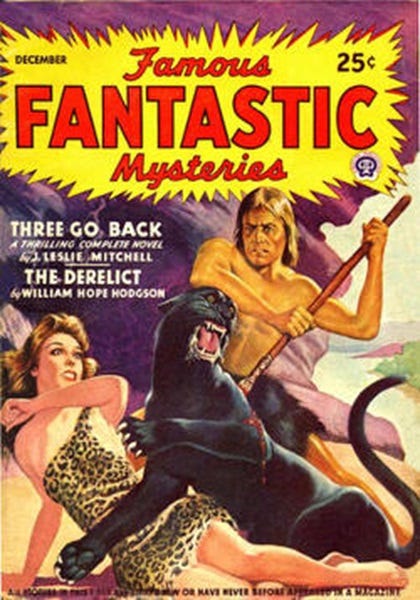

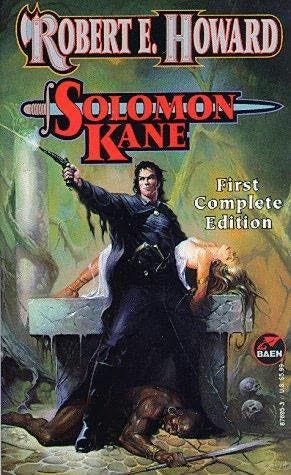

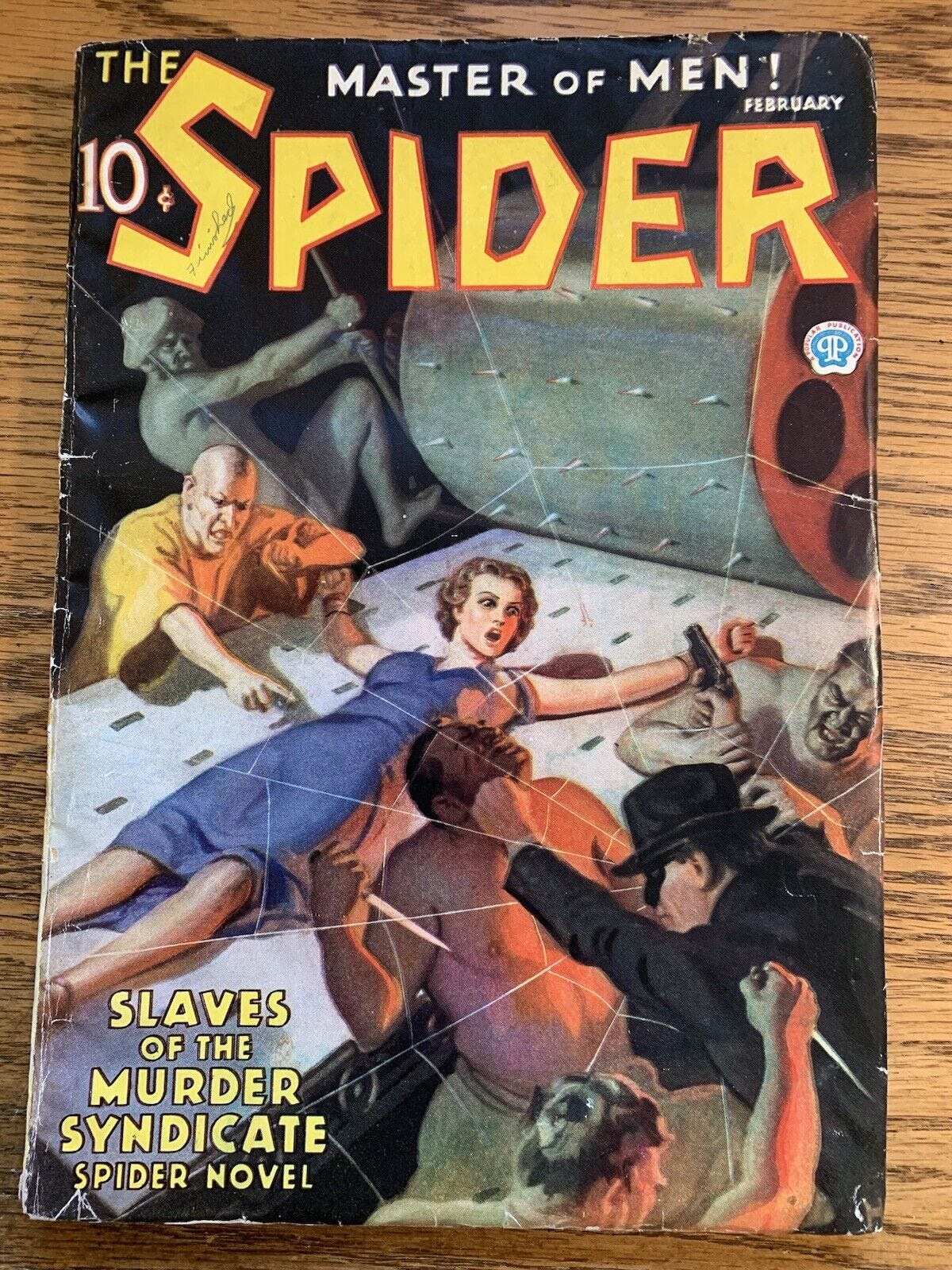

Let’s look at some more cover art from back when MAF could be found on book shelves, news stands, and spinner racks.

Common theme is a woman in danger, right? Publishers were tapping into basic psychology to entice readers to open the book or magazine: a man’s natural protective instinct toward women. This very instinct, in a warped state, is what drives White Knights to blindly charge to the rescue when some dastardly villain endangers a feminist’s delusions.

That the cover art damsels were almost always attractive, showing some skin, tapped into another primordial instinct still being exploited to this day.

Putting a woman in danger is such an effective draw that the most famous silent movie serial of all time, The Perils of Pauline, was named for such. In the early days at least, the Lois Lane character’s primary purpose was to get herself in dangerous circumstances it would take Superman to get her out of.

If the artist decided to spell it out a little more clearly, they would include a man in the image (as a stand-in for the reader) in a position to rescue her.

Yup: wish fulfillment fantasies—which are fundamentally immoral if they satisfy heterosexual men, but perfectly valid for everybody else.

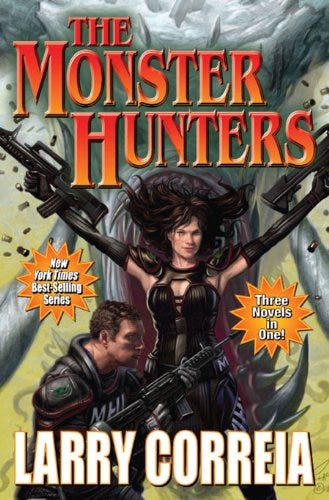

Now let’s look at some Monster Hunter covers:

Does anything, y’know, kinda’ sorta’ stand out that’s rather a departure from the MAF tradition?

These badass macho chicks don’t need no man! I’m sure they can handle their own oil changes, too.

I don’t consider MHI to be men’s adventure fiction.

But here’s an embarrassing self-own: after considering the metrics that define MAF, I realize most of my own novels don’t qualify, either. Not for all the same reason as MHI, obviously. Mostly because, even though I write a lot of action sequences, the action is not usually the priority. I often spend more time on characterization than the MAF writers/editors thought necessary. Stuff like that.

Most of my fiction is better described by the genre term I coined about 15 years ago: “dude lit”—a broader umbrella category which includes MAF, most pulp, and pretty much every book written by, for, and about men. It should probably include purpose-written boy’s fiction, too. (It’s my term, so I can modify it however I want.)

There is a distinction to be made between dude-lit (fiction by, for, and about men) and “men’s fiction/men’s adventure fiction.” Of course, both differ significantly from unisex fiction—which is as masculine as tradpub gets.

Excellent write-up. Thanks for sharing the AI regurgitation—and your two very pertinent additions: No gender confusion, and a strong element of masculine protection/rescuer. Spot on! I also love your selection of covers. (Frazetta is one of my favorite artists.)

I’m a female, but the sort of story you describe is mostly what I enjoy reading or watching. The feminist garbage has ruined every genre. I definitely prefer masculine men rescuing or protecting damsels for my entertainment. It makes every genre better when women are feminine and men are strong!

Let me do the usual thing in this sort of thread: hawk my latest book The Lives of Velnin https://brianheming.substack.com/p/the-lives-of-velnin by comparing it to the metric.

* Endless action (check)

* Rescues damsel in distress repeatedly, who needs rescue. (3 times in chapters 1, 2, and 3, and later.) (Check)

* Lack of romance--No. Instant romance with said damsel.

Fundamentally, in absence of well-paying publications purely catering to Men's Adventure fans, it's expedient even for authors of action-adventure-girl-rescuing stories to put in a romance, and the rescued-damsel is the obvious choice. Such romances create a secondary appeal to girls and women who like books like The Princess Bride, and remain appealing to men if not done in too long-winded a way.

Note that I did not try to Amazon-categorize this as Men's Adventure, because it fails the critical metric of "is like other books in that Amazon category, which is now a cesspool." Instead it's Coming of Age, Swords & Sorcery, Adventure Romance, and Royalty Fairy Tale in some combination/selection.