When I was a child, I simply accepted the status quo and rarely questioned it. (No doubt plenty of folks wish I was still that way as an adult.) Something I never questioned as a kid was the purpose and need of superheroes in the world depicted in comic books.

The purpose of superheroes was to fight crime. Superheroes were needed because dangerous criminals…sometimes super-criminals…were interrupting law and order. Left unchecked, those colorful criminals would destroy the very fabric of a civilized society…or something.

We needed Spiderman because nobody else could stop Electro or the Vulture from robbing banks. We needed Batman because only the world’s greatest detective could solve the Riddler’s clues, or foil the Penguin or Catwoman’s art gallery heist, then vanquish their armed henchmen with his bare hands (and utility belt, sometimes).

(Of course the Justice League, Avengers, etc. typically faced much more powerful threats—evil demigods out to destroy the world, usually. But that level of threat, in real life, can’t be neutralized with heat vision, repulsor rays or a magic hammer. So I’ll shelve that comic book trope for a possible future analysis.)

A superhero would logically focus on the most dangerous threats, right? However, an intelligent, honest person is unlikely to observe our current reality and determine that the most serious atrocities plaguing civilization are bank robberies and art gallery heists. Those aren’t very relevant now and, frankly, they weren’t when I was a kid reading comics. But like many illogical tropes, that escaped my scrutiny when I was a child.

Crime is a deadly serious problem in our world, to be sure. The volume of low-level crime is destroying our real life Gotham Cities, and could easily be stopped by the Mayor and Commissioner Gordon—but the mayor and commissioner are doing everything in their power to make it worse, not better.

Moreover, the worst and most prolific crimes in our reality are committed by those collecting government salaries.

Why are myopic superheroes (or, more accurately, their myopic writers) focused on stopping bank robberies and art gallery heists when such crimes are not even in the Top 100 List of crime pushing our civilization over a cliff? Well, today it’s because the mainstream comic industry is run by lying, perverse, incompetent propagandists incapable of critical thought. But why was that the focus even before the inmates took over the asylum?

Laziness and complacency might be factors in the equation. You can chalk some of it up to the fact that anti-crime narratives are not controversial. Those are safe stories to publish. Little connection to reality, but then, same deal with masked do-gooders who fight criminals pro bono in garish tights and capes. The incredible nature of the genre lends cover to this radical departure from reality and relevance.

I submit that the more substantial motive was simply tradition. Writers at the Big Two in the ‘80s stuck to the crime tropes because the writers they replaced had done it. And those writers did it because the writers before them had. And so on. But when and why did it start?

To answer that , we have to revisit the decade before the debut of the first comic book heroes. That places us in the Prohibition years—a time almost as lawless as modern day San Francisco or Portland—at least public perception at the time imagined it was that out-of-control. Low-level hoodlums (often immigrants or the children of such) rose to rule over vast criminal empires; rival mobs battled each other for turf; and the authorities were so corrupt that Elliot Ness reported bootleg liquor was bought and sold even in the Chicago Police stations.

Growing through their rising adult phase of life (age 20-40) during this social unraveling was the Lost Generation—a rowdy, independent, cynical breed that wasn’t entirely appalled by the urban lawlessness of the times. In fact, some of them romanticized the bloody exploits of the Capone or Luciano gangs (for instance). Even more romanticized were the early Depression era bank-robbers like John Dillinger, “Baby Face” Nelson, and Bonnie & Clyde.

Politicians made stupid laws and had sent Americans off to die in a pointless European war, police were corrupt, and outlaws (be they gangsters or bank-robbers) who stuck-it-to-the Man were not so bad, by contrast. They were often perceived as modern Robin Hoods, or antiheroes at worst.

All during the Roaring ‘20s, there was a backlash brewing against this nihilism—both the behavior and the attitude. Maybe an early portent of a coming sea change appeared in 1927, when the first Hardy Boys novels were published. The books were written for juveniles, and featured teenage amateur detectives solving mysteries and catching criminals. The success of the series proved that literature could be harnessed to give the next generation a more traditional understanding of right and wrong.

Speaking of the G.I. (“Greatest”) Generation, they were already markedly different from the Lost. They were the “good kids”—optimistic, confident, collegial, and civic-minded. But their parents, and society as a whole, were not taking any chances. These kids were going to be taught, by every single institution, to trust in authority, and that outlaws were bad guys.

Elliot Ness and his “Untouchables” were real-life heroes for this new generation. Al Capone and his entire mob were the embodiment of everything wrong in the world. In radio, the movies, juvenile novels, the pulps, and in comics, this good vs. evil matchup would be exaggerated to iconic boilerplate.

When he was just a narrator for a radio drama series…before he himself even became a character…The Shadow’s voice warned young boys in living rooms across the country, “The weed of crime bears bitter fruit. Crime does not pay!” For those youngsters who were reluctant to read The Hardy Boys or similar prose novels (illiteracy was far less common then than now, despite what the government and media tell you), Dick Tracy debuted as a newspaper comic strip in 1931, using cool futuristic gadgets and government sanction to enforce law and order.

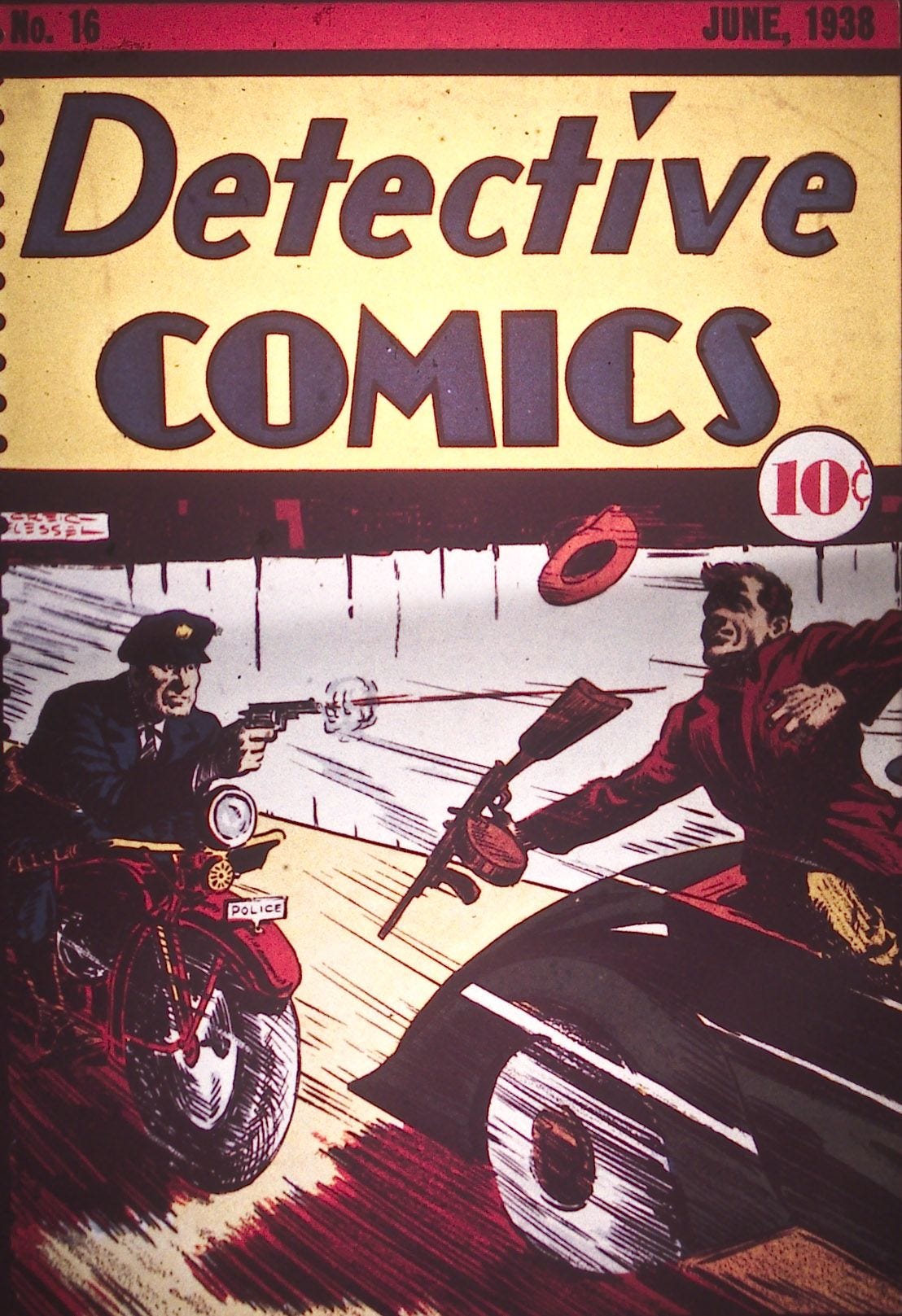

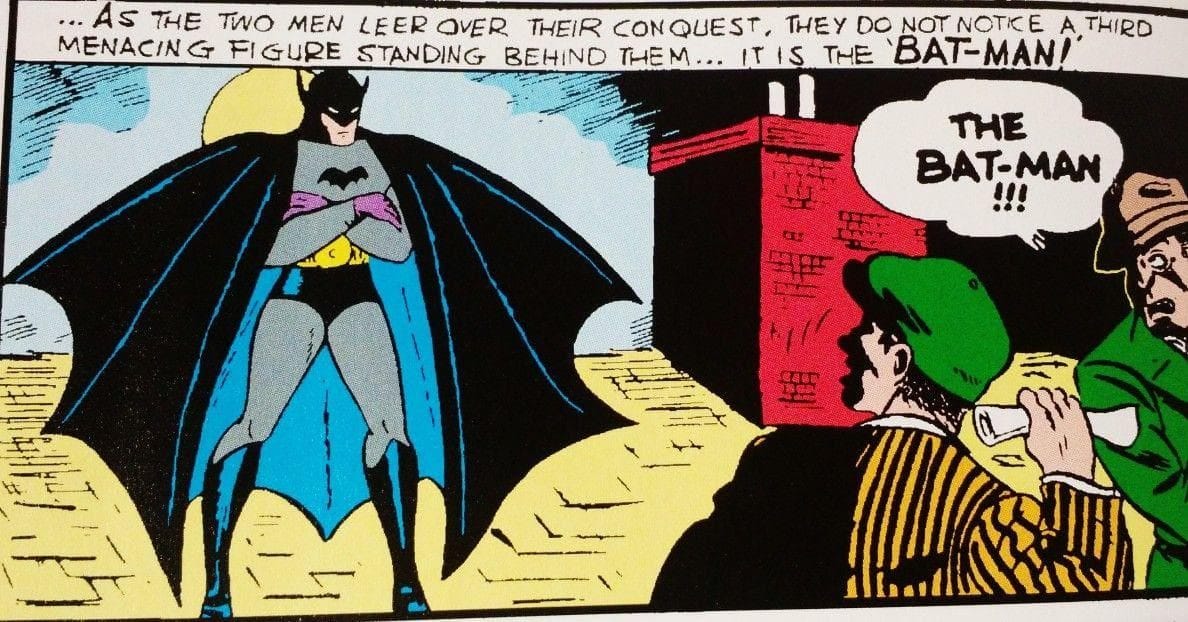

The romanticized “Robin Hoods” of just a few years earlier…gangsters, bank-robbers and other outlaws…were unfailingly depicted as villains, headed ultimately for prison or an early grave. The heroes were now G-Men, “ace reporters” and detectives. So popular were the latter that 26 issues of Detective Comics were published before The Batman made his first appearance.

Joe Blow during the New Deal era, knowing nothing about Generational Theory and the historical cycle, assumed the youth of America would remain on the same delinquent course as the Lost Generation, growing worse and worse, year by year. Parents and society at large was desperate to avert that course. “Law and Order” narratives then might have almost been as obligatory as LGBT-pandering is today (for the polar opposite reason—the goal then was to strengthen the moral underpinnings of America, not obliterate them).

Comic creators pitched in and did their part during the Crisis/4th Turning (Great Depression and WWII) to correct the rebellion of the Unraveling/3rd Turning (WWI and the Roaring ‘20s) and herd young boys onto the Straight & Narrow. Superman intervened to mitigate natural disasters in the early days, but pretty much kept busy catching criminals.

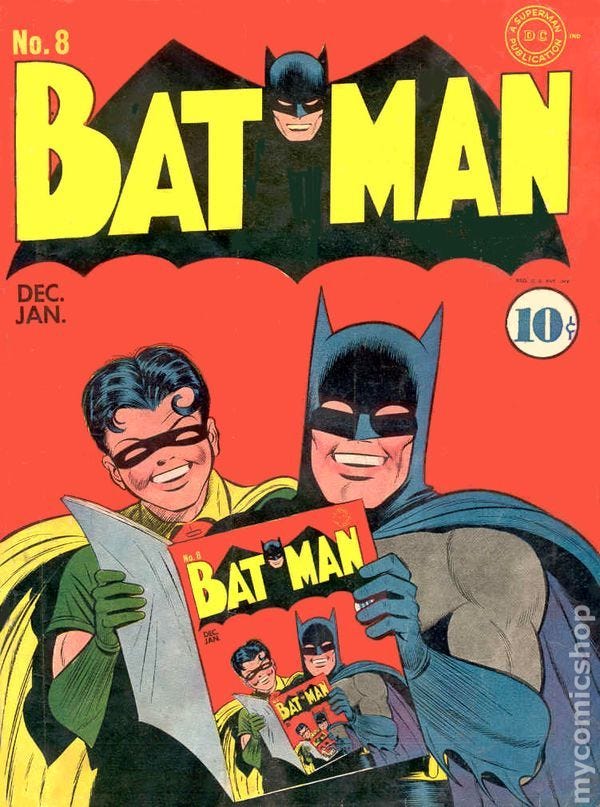

The Batman did nothing but fight the underworld during the Crisis, but did so with the brutal efficiency of a Lost Generation vigilante at first. He didn’t just strike fear into the hearts of criminals, but also the hearts of the Karens of yesteryear—no doubt inspiring epic pearl-clutching whenever they came across his stories. He had to be toned down and lightened up. The black on his costume turned to blue. The “bat ears” on his cowl were shortened to less of a safety hazard. He was drawn to resemble a friendly masked pro wrestler, not an avenging nocturnal predator. He began to appear in broad daylight, and worked with the police, losing his Public Enemy status in Gotham. He bore a friendly smile. Most significantly, he was paired with a garishly-costumed boy sidekick, making him a surrogate father.

That’s how the Batman was made respectable. Now he was now just “Batman,” with no “the.”

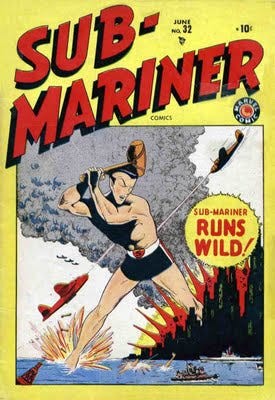

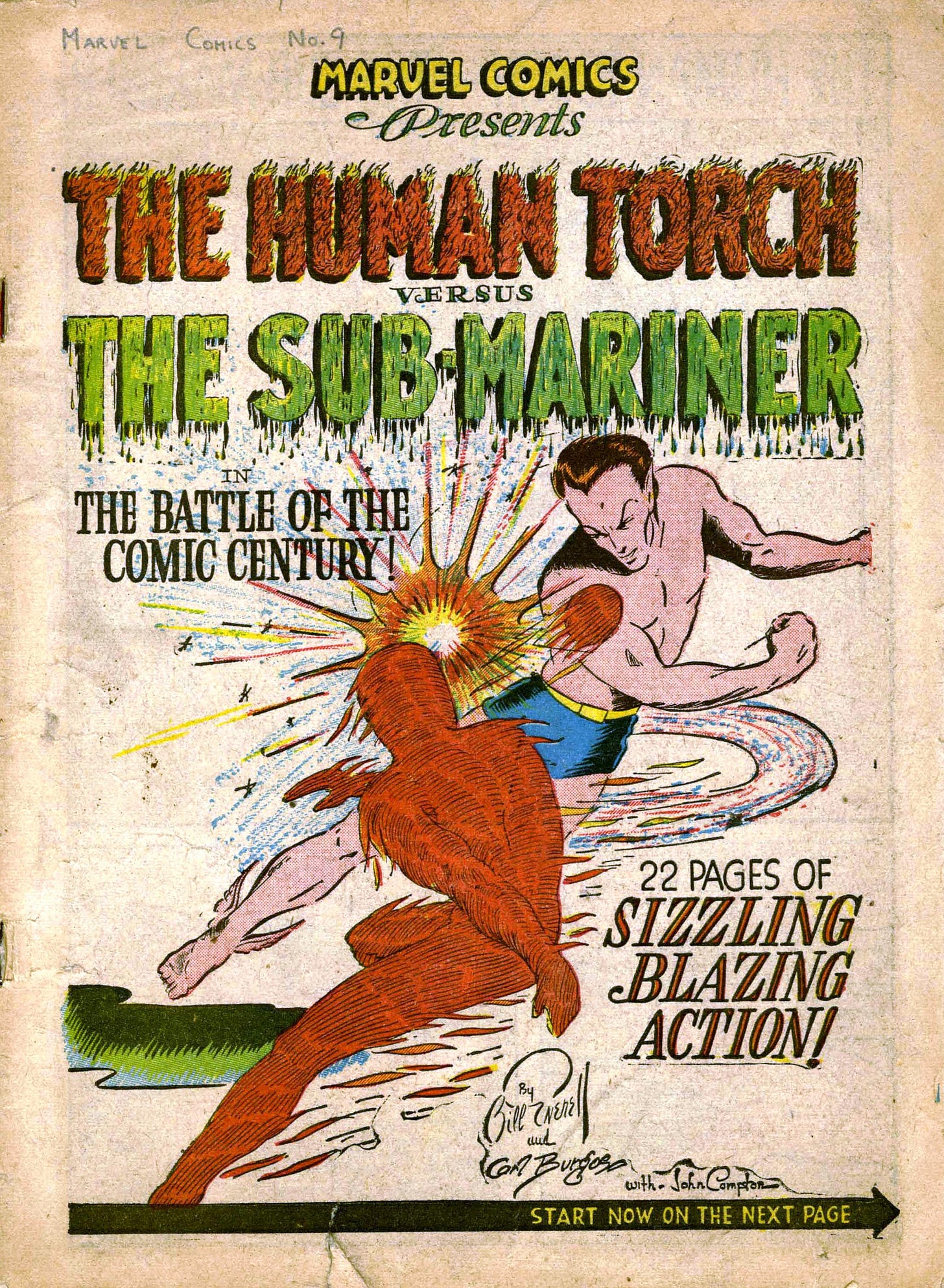

If ever there was a poster child for the Lost Generation, it was Namor, the Sub-Mariner, in the early Golden Age. He was a cynical, nihilistic anarchist in his early days, with super strength, a flair for destruction, and the ability to fly before even Superman found it.

The creators had created their own Frankenstein, and needed to counterbalance him somehow. So pressing was the need, they custom-built a nemesis for Namor: a “synthetic human” conceived and birthed in a laboratory. He would have the power of flight as well, and while the Submariner drew his superhuman strength from water, the Human Torch could command…in fact, could transform into…fire.

The Sub-Mariner was an agent of Chaos. The Human Torch, of course, was emblematic of Order. Custom-made for it, literally. It didn’t take him long to officially join the Police Force. The Torch kept Namor in check until the War came along and the Sub-Mariner projected his antisocial fury onto the Axis. By that time, the paradigm had shifted. Some chaos and destruction was necessary to inflict on foreign enemies.

All the comic book heroes did their part in the war effort—mostly catching spies and saboteurs on the Home front. Just like most of their readers by then (who were not yet old enough for military service), the costumed crimefighters had to stay home and let the real heroes resolve the crisis.

The war years temporarily altered the paradigm, but after V-J Day, superheroes went back to apprehending criminals. Heroes who were overpowered or otherwise unsuited to auxiliary police roles mostly lost their audience. The Sub-Mariner, Captain America, the Specter and even the Flash retired from the news stands. Most comic book heroes gave way to horror, sci-fi, western, and romance comics. Captain Marvel and Superman survived (at first) by battling criminal masterminds. Even Wonder Woman tackled criminals instead of Roman gods and Nazi generals. Batman never lost his stride—outwitting criminals just as before America’s entry in the War.

The Prohibition Era gangs in real life suffered a fate similar to the costumed heroes in comics. Most of them faded away, leaving just a handful of major crime families to rule over the Underworld. Organized crime still existed, but the times had changed. Mobs rarely engaged in turf wars anymore, to determine who would control what racket. Certainly nothing as dramatic and in-your-face as the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. Bank robberies and other heists occasionally took place as well, but not like the fabled crime sprees of the Depression.

Yet those Golden Age crimefighting tropes continued in the comics. The Cold War, the Soviets getting the Bomb, and Red infiltration of the government may (should) have been the real world concerns in the postwar years, but in Gotham, the next art gallery heist by Two-Face or the Joker was the real threat.

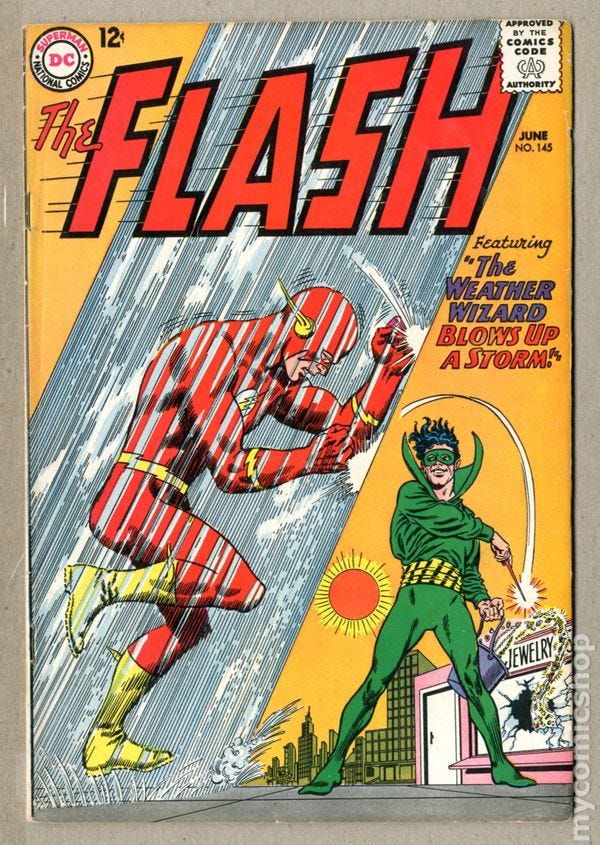

The Silver Age of comics began the very same year the CIA left Hungarian freedom fighters holding the bag, to be crushed by the Red Army. The Flash was reincarnated, with a new look and a new secret identity. And what was his mission? Matching wits with Mirror Master, the Trickster and Captain Cold to foil bank robberies and art gallery heists. But as anachronistic as the “War on Crime” trope was in 1956, it is even less relevant today.

Certainly the criminal Underworld still operates, but is composed of individuals who are simply not evil enough to be allowed to hold public office. Mobsters are apprehended and imprisoned only when their organizations compete too effectively with the criminal enterprises that serve the “respectable” institutions in our erstwhile republic. Otherwise, “Law Enforcement” takes a knee. Our Orwellian “Justice System” exists to protect criminals and persecute those who try to protect themselves (and others) from those criminals. Also targeted are citizens who dare expose the inversion of justice…which is exactly what “ace reporters” would be doing today if they had any modicum of integrity and courage.

The real-life Lois Lanes and Vicky Vales are part of the problem—a big part. Trusted institutions commit the crime, and the Press covers it up. Know who else is part of the problem? The superheroes. If Batman is sanctioned by the Gotham Police to “fight crime” in the Current Year, and cooperates with Commissioner Gordon, then he is as corrupt as Two-Face. If the Dark Knight were actually heroic, and dedicated to justice, he would be throwing politicians into vats of chemicals. If Captain America was dedicated to America, he would throw the DHS Czar out of a helicopter onto the hordes of foreign invaders sweeping over our border and coming to a neighborhood near you.

Prohibition was nothing compared to the dystopian hellhole we are sentenced to. When laws are selectively enforced, there is no law. These are truly lawless times and we are ruled by lawless cutthroats. Right and wrong mean nothing—all that matters is power. The criminal ruling class loves power and uses it. Good men are afraid to use it. If superheroes existed and were truly super heroes, they would be using their superpowers to fight against this lawlessness. The comic book characters from the Big Two don’t, because the writers and editors at Marvel and DC condone what’s being done to us. The comic book characters from the indie creators won’t do it because of fear, or because they’ve been programmed to believe it’s immoral to fight back in the Culture War. Only people who hate us should be allowed to employ social or political commentary in the arts, you see.

The crimefighting trope is beyond silly, today—it’s ridiculous.

There’s nothing wrong with escapism, but what the Big Two are publishing is not escapist—it’s agitprop printed in service to the lawless regime ruling over us, betraying us, stealing from us, and replacing us. The superhero content written by independent creators will remain hopelessly irrelevant for as long as they continue regurgitating the archaic crimefighting trope.

Thanks for reading! This won’t be the last time I write about comic book superheroes. God willing, some of my graphic novel scripts will be mated with artwork in the near future.

Hey, check out my other stack: Henry’s Sneak Peeks, where I’m currently sharing chapters (for free) from the first book in my Paradox Series: Escaping Fate. This particular novel is a coming-of-age time travel sports adventure.

"See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil," isn't that how the old saying goes? That's the current crop of comics writers who, for political reasons, cannot go after the real villains in their stories. This is a shame, because great material is left on the table, so to speak, but on the other hand, it's an opportunity for us working in the independent scene to pick up the slack.

Great essay I think what is also annoying is the lack of ending/conclusion to the story that being said, the trouble with the superheroes is exactly as you described; the chase the robbers thing and never deal with other sorts of plots.

What I always recommend these days is Comte de Monte Cristo which lies at the origin of the genre but doesn't play by its rules and operates somewhat differently yet similarly without the bank robbery stuff.

That said I wonder what your ideal superhero tale would be? Something like the Mask of Zorro/Comte de Monte Cristo? Something more like Superman 1976? A story like No Man's Land from Batman? The Shadow?

Brilliant essay is there a third part?