The Golden Age comic creators established a new mythology. Probably not for the same purposes that ancient mythologies were developed—you won’t find the Temple of Wolverine in a neighborhood near you, nor are there worshipers of Black Canary, cosplay fan service and comic conventions notwithstanding. This new mythology was (ostensibly, at least—read my last article if you haven’t already) all for the sake of entertainment.

As awful as most of the writing was in those days, the writers were fairly well read. Perhaps it’s difficult to believe in today’s disposable culture, but people back then didn’t assume everything lost all value once it aged a few months. The average American back then was at least somewhat familiar with classic mythology. Some early comic creators must have known they weren’t just borrowing from the ancient myths, but assembling new ones, clad in capes and tights.

One of them was young Stanly Lieber, who would later become famous by his pseudonym, Stan Lee. At the dawn of the Silver Age of comics, Stan, his brother Larry, and Jack Kirby deliberately leaned into mythology (specifically, of the Norse variety) and transplanted the Viking god of war into the comic medium. Thor was given a more modern comic book wardrobe and aspects of the lore were tweaked and streamlined. It’s not plagiarism if any presumed copyright expired a millennium ago, right?

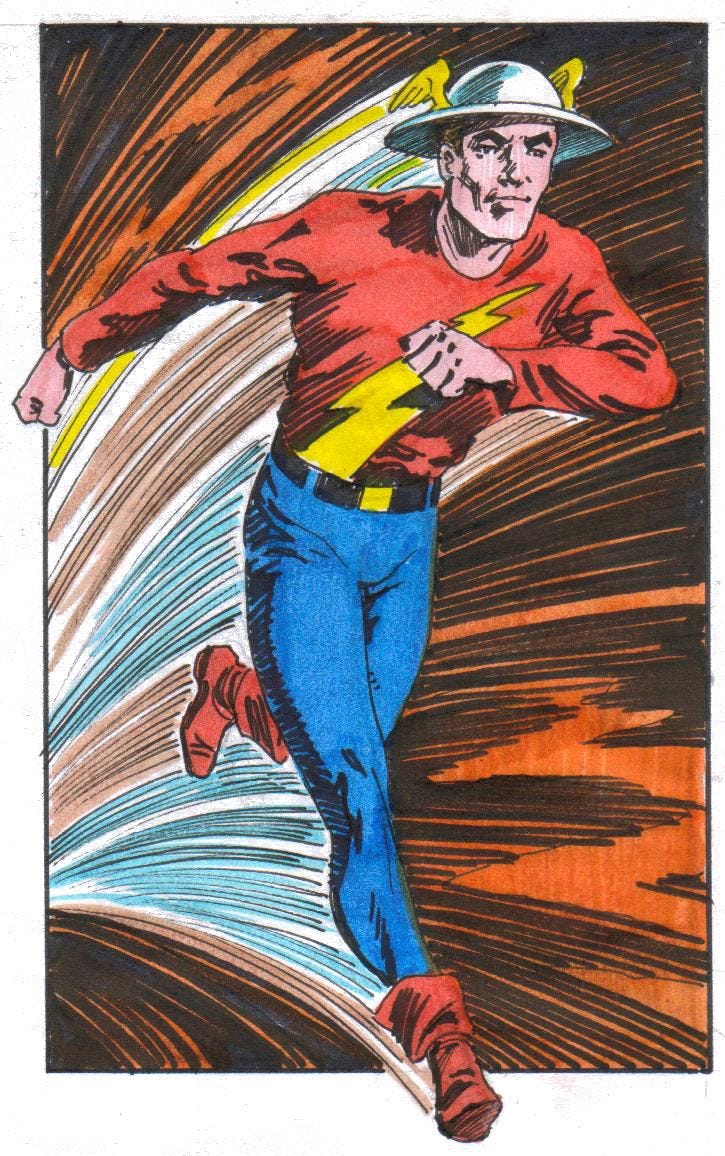

Going back to the Golden Age, the original Flash wore some headgear that resembled the hat/helmet worn by the messenger of the gods (Hermes/Mercury) in artists’ depictions. (I read somewhere that technically, it was “Winged Victory” who wore that winged doughboy helmet, for the record.) But that is, perhaps, a tenuous connection.

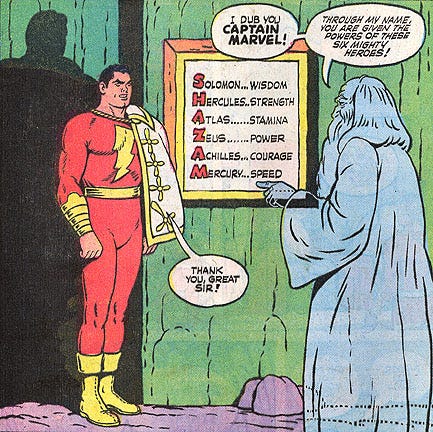

More pronounced is the mythological roots of the original Captain Marvel. The magic word (which was also the name of the wizard who bestowed his gift) that could transform him from young Billy Batson into the World’s Mightiest Mortal was an acronym that signified the godlike powers he was endowed with. Aside from the first one, the letters stood for Greco/Roman heroes and gods: the strength of Hercules, the stamina of Atlas, power of Zeus, courage of Achilles and speed of Mercury.

When William Mouton Marston endeavored to develop a “female Superman,” he lifted the character concept directly from Greek mythology. “Diana Prince” (ever wonder why it’s not “Princess”? Hmm…) was an Amazon—one of the mythical warrior womyn who could defeat men in combat. As I mentioned last time, it was common for Wonder Woman to interact with the gods of myth in those early stories, as well as her 2017 eponymous movie. The exclusively female island she came from was also from Greek myth. In post-Golden Age reboots of the character, her origin was revised to be even more blatantly mythological (or sacreligious, depending on your faith): her “mother” formed a statue of her out of clay, then animated it with some sort of pagan magic.

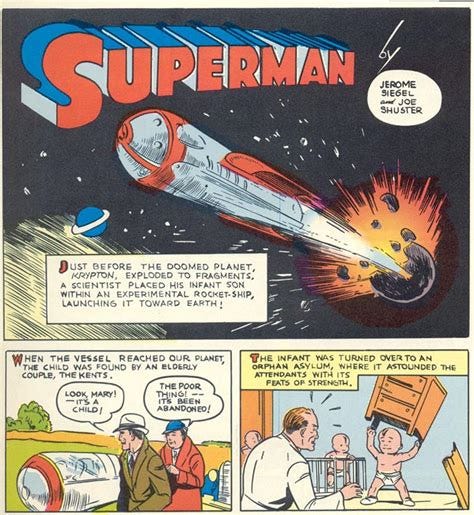

What about the first comic book superhero? His name wasn’t derived from ancient mythology, and he didn’t hail from Mount Olympus, but over time he became the equal of the gods of myth. Most armchair historians of comic fandom know Siegel and Shuster “borrowed” ideas from several sources to develop Superman. They visited Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Barsoom to, at one point, partially explain the Kryptonian’s strength and ability to leap tall buildings in a single bound (later fly) via the lighter gravity on Earth. They snuck into Doc Savage’s Fortress of Solitude to clone the Man of Bronze for their Man of Steel. But what I noticed first was the similarity of his origin story to accounts, not from mythology, but from the Pentatuch.

Long before my first serious attempts to read the Bible, I had watched The Ten Commandments (1956) several times on TV. When I read how Jor-El and his wife bundled little baby Kal-El into a miniature rocketship and launched him into space to escape the destruction of home planet Krypton, the similarity was unmistakable to me: baby Moses bundled in a floating basket and sent down the river to escape Pharoah’s holocaust against the Hebrew boys in Egypt. Both landed among a foreign race, were adopted by benevolent parents , and raised as citizens.

As Jewish boys in the 1930s, it would be very odd if Siegel and Shuster were not at least familiar with the accounts in Exodus. And I seriously doubt that the “El” suffix in Kryptonian names was a coincidence. You might already know that the syllable means “god” in Hebrew. You find it in so many names: Israel (“He wrestles with God.”); Michael (“Who is like God?”); Daniel (“God is my judge.”); El-Shaddai (“God Almighty.”); etc. What I didn’t know for many years is that “El” doesn’t always necessarily refer to the Creator God. The pagan gods often also had this sound in their names: Beelzebub = “god of the dwelling” or “lord of the flies.” (“Babel,” the name of the city with the famous tower, might be a double entendre—not just a transliteration of “babble,” but also meaning “god gate,” as in a dimensional portal to the heavens, or unseen realms.)

The Bible acknowledges the existence of pagan gods—despite generations of priests and preachers insisting otherwise (adding to and taking away from the content of scripture in doing so). The acknowledgment is hiding in plain sight—and I don’t mean just idols/statues. The First commandment, to paraphrase the King James translation, says “You shall have no other gods before me.” Going back to the Exodus story, there were several plagues, or judgments, in Egypt before Pharoah agreed to let Israel go. Pharoah’s magicians were able to duplicate many of the plagues. These men were not the illusionists we think of when we hear the word “magician.” They were bona fide sorcerers. The supernatural power they exercised came from somewhere. Where it came from is revealed when Moses (the stenographer of the first five books of the Bible) says that the plagues in Egypt were El-Shaddai’s judgments against the gods of Egypt.

In a high school English class, a teacher once told me and my classmates that the Bible was plagiarized from Greco-Roman mythology. What I understand now is that it was the other way around. The Old Testament was mostly written before the Greek Empire began to form. The Book of Job was complete before Israel became a nation—while it was merely growing into a clan. But even before that, the accounts that would one day form Genesis were passed down orally from the very beginning—predating all of the pagan mythologies. There are scholars who have done a far more thorough job of documenting the history than I will attempt here.

With that in mind, let’s consider the most prominent superhero from ancient times. Of course I mean Hercules—known as Heracles to the Greeks. We know he was endowed with superhuman strength. The source of that power was his DNA. He was, quite literally, a hero of old. The “heroes” of Greco-Roman mythology were a hybrid species bred from male gods and human females. Exactly like the nephilim (gigantes in the Greek, often translated “giants”) mentioned in Genesis Chapter Six. In another paraphrase from the King James translation, those were “the heroes of old; men of renown.”

In one of Heracles’ exploits, he spent three days in the belly of a sea monster. Much like how Jonah spent three days in the belly of a great fish. Many legends have some basis in fact. The crazy myths passed down from ancient times (and not-so-ancient times, such as the Nazi obsession with the Aryans—a mythic race that inhabited Atlantis, as Aquaman and the Submariner did after the fabled city sank) and the universal qualities they share across languages, cultures and epochs make sense if you allow that they may have been based loosely on a lost, nigh-forgotten reality, alluded to in Genesis Six and other passages from the Bible.

Like a baby boy escaping death (hence his nation living on through him) by being placed in a small vessel and launched into the unknown.

Going back to Solomon, what all this proves is that there is nothing new under the sun.

If you enjoy superheroes, and/or find my take on them interesting, go check out my other stack, Tales of the Earthbound. I’m posting episodes from the first graphic novel in an epic series, and you can read them for free!

Add "serious read of bible" to the todo list...

Babel means god gate??? That is so creepy, I never knew that! Thanks for this article, it was super interesting.